This piece is taken from Mizanplas #1: Japan and Spain, a new magazine dedicated to thoughtful writing on wine, gastronomy, and travel. The debut issue brings together stories and reflections from Japan and Spain. You can purchase the magazine at: mizanplas.com/store.

By Can Seven

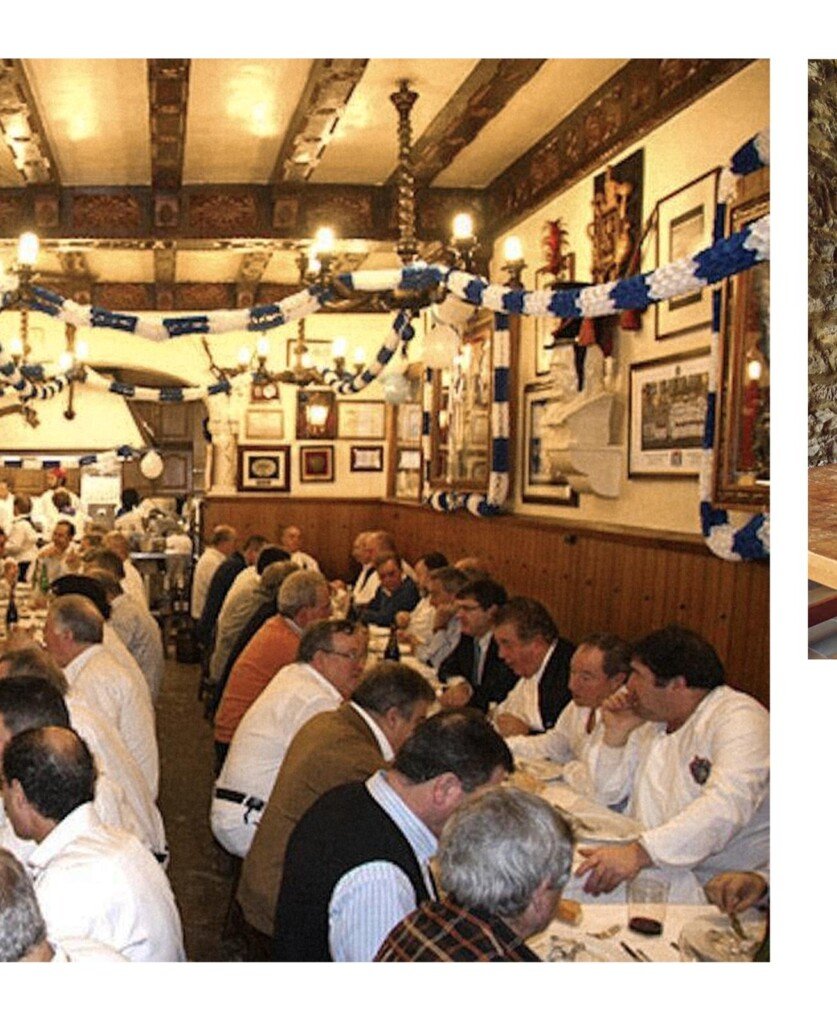

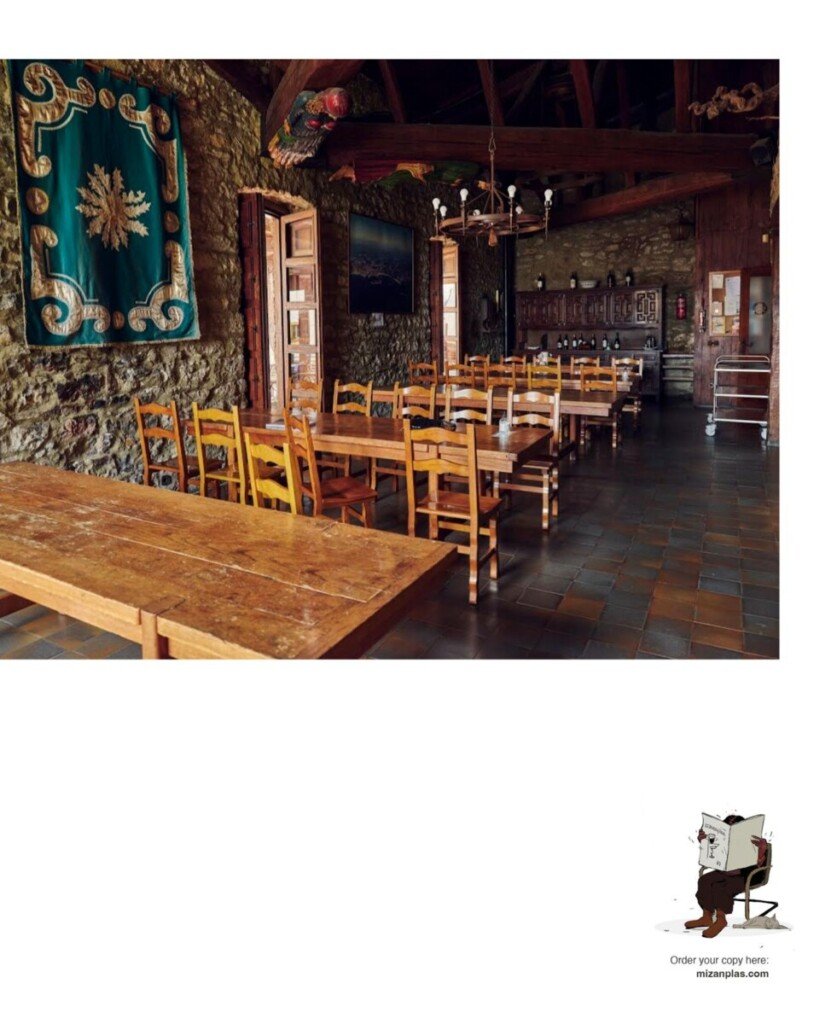

Years ago, on a warm August day in San Sebastián’s historic Alde Zaharra district, two friends and I began descending the stairs behind a wooden door. As we went down, the shouts of tourists – mostly in English and French – faded, replaced by a chaotic mix of laughter, Basque and Spanish. The sea breeze’s scent of iodine gave way to the irresistible aroma of roasted peppers and txuleta. Behind long, hand-carved wooden tables and benches, a large professional kitchen came into view. This wide hall wasn’t a restaurant or a bar – it was a Sociedad Gastronómica, or, as it is better known, a txoko. Though I had heard about them many times before, it was my first time stepping inside one – and, just as for so many living in the Basque Country, it didn’t take long for it to become a central part of my life.

At the bottom of the stairs, some of the friends we had arranged to meet for lunch were already setting the long table – easily large enough for twenty people. By the fire, two others, wearing aprons embroidered with the emblem of their txoko, were busy preparing the starters. Since that day, I have eaten, drunk wine, joined meetings, watched football matches and attended parties at dozens of different txokos. Each new one I visited left its mark in its own way. But above all, the smell of food that greeted me at the bottom of those stairs that first day still lingers in my memory – it remains, for me, the very essence of what a txoko is.

So, what exactly is a Sociedad Gastronómica?

In Basque, the word txoko literally means “corner.” It is used to describe warm, cosy places where people enjoy spending time. These venues are usually organised as private clubs or societies. Txokos are run by committees and presidents elected by their members, and they operate on a non-profit basis. Their purpose is to provide a space where members can cook, drink, socialise and gather with their cuadrilla – their circle of friends.

There are over 1,500 txokos in the Basque Country. While their statutes may differ slightly, they generally function in much the same way. Though these are members-only spaces, members are free to bring along as many guests as they like. All they need do is reserve the space in advance. They also have to bring their own ingredients for cooking. As for drinks – wine, cider, beer or soft drinks to go with the meal, or digestifs such as Patxaran and coffee afterwards – these are provided from the txoko’s cellar or fridge. Apart from the annual membership fee, the only cost members incur is for the drinks they consume.

One of the core principles at the heart of txokos is trust. That is because in nearly all of them, there are no waiters or chefs. In other words, it is up to the members themselves to ensure that any drinks consumed are paid for – honestly and without supervision. I should pause here to emphasise: the fact that txokos are such an integral part of Basque social life owes much to the region’s deep-rooted sense of community and the strong trust that binds its people together.

Beyond these general structures and rules, each txoko is unique – shaped by its size, history, reasons for gathering, annual fees, range of services and social function. Some were founded by members of the Christian Democratic Basque Nationalist Party (Partido Nacionalista Vasco, or PNV); others by those aligned with the Izquierda Abertzale tradition of the Patriotic Left. There are txokos for horse-racing enthusiasts, and others formed by professional groups such as fishermen. Some have been running in the same location since the 1800s, while others are relatively new. In some, after cooking and eating, you clear your table but need not wash up, as dishwashing is handled daily. In others, you are expected to do it all yourself. Some txokos screen Real Sociedad or Athletic Bilbao matches every week, while others do not even have a television. There are those located in basement spaces, and others that occupy entire four-storey historic buildings. In some, the annual membership fee is €150 – while in others, the initial joining fee alone can be €1,500.

The History of the Txokos Is Also the History of San Sebastián

To truly understand the phenomenon of the Sociedad Gastronómica, one must look not only at the Basque way of life, but also at the history of San Sebastián (or Donostia, in Basque), the city where txokos first emerged. The earliest written records refer to a monastery named San Sebastián, founded in the 11th century. Donostia–San Sebastián rose to prominence in the 12th century as a walled port city within the historical Basque kingdom of Navarre. Over the years, it became a frequent stage for battles and treaties between the warring kingdoms of Navarre, Castile and France – its military and commercial importance growing steadily. San Sebastián came under the rule of the Kingdom of Castile in the early 1200s and remained enclosed within its medieval walls until 1863. Another turning point in the city’s fate came with the demolition of those walls, followed shortly after by Queen Maria Cristina of Spain choosing San Sebastián as her residence in 1855, following the death of her husband, Alfonso XII.

Until the 19th century, San Sebastián led a modest urban life. But as the city walls came down and Queen Maria Cristina began spending her summers there, the European aristocracy and bourgeoisie – having discovered the health benefits of sea bathing – started flocking to San Sebastián as well as to Biarritz. The city began to transform. Until then, the social spaces of the inhabitants living within the narrow confines of the old city walls had been the cider houses – known as sidrerías or sagardotegi in Basque – and the traditional Basque bars, the tabernas. But the changes now under way were bringing a form of gentrification to the very heart of the city.

It was precisely in this context that txokos emerged – as both a social response and a practical solution to rising prices, the shifting nature of public gathering spaces, the displacement of cider houses to the outskirts, and new restrictions placed on the tabernas.

In their earliest days, these spaces were strictly male-only – women and children were entirely excluded. They quickly became primary social hubs where men, who often worked long hours, could spend time away from both work and family. Compared to the crowded and expensive tabernas, which had fixed opening and closing times, these new venues – non-profit, cheaper, free from crowds, and with hours determined by the members themselves – gained immense popularity.

The Present and Future of Txokos

Over the years, and in response to shifting social dynamics, txokos have naturally evolved – and today they are no longer just places for cooking and eating. They now host everything from sports events and community activities to mutual aid efforts. Even the drums that echo non-stop for twenty-four hours during the city’s most important festival are carried on the shoulders of these communities. One of the most significant changes – barring a few exceptions – is that txokos are now open to women as well.

Though the aristocratic and wealthy European visitors of a bygone era have been replaced by American, Asian and European tourists and young surfers; though what was once Europe’s most popular casino has given way to Michelin-starred restaurants; and though grand theatre productions and operas have made room for the San Sebastián Film and Jazz Festivals – txokos remain one of the most vital social spaces for the Basque people, many of whom live in small flats or scattered baserris (farmhouses). Yet txokos serve a purpose beyond that: for those who place food at the centre of their lives – and especially for cooks and chefs who pursue it professionally – they act as culinary hubs, places to compare recipes, exchange techniques and learn from one another.

From the fisherman to the butcher, the barman to the labourer, the Michelin-starred chef to the one who cannot even crack an egg at home – everyone gathered around that long wooden table becomes a valued member of the community and, around the fire, a cook in their own right. I only truly realised how unique this “transformation into a chef” – something I had come to take for granted – was to this place when I took some guests from the United States to a txoko in Hondarribia. One of them, a passionate food lover, was so impressed by the Donostia-style monkfish we had eaten that he asked Andrés, the man who had cooked it: “Which restaurant are you the chef of? I’d love to visit.” Andrés, who regarded the quality of his dish as the most natural thing in the world, gave a reply that surprised my guest and made me smile: “Chef? I’m a carpenter.”

They say the Basques have three existential questions: “Where does our language, Euskera, come from?”, “Who are we, the Basques?”, and “What’s for lunch today?” If you ask me, whether you are a linguist, an anthropologist or a cook, one of the best places to seek answers to all three is surely a Sociedad Gastronómica.

This piece is taken from Mizanplas #1: Japan and Spain, a new magazine dedicated to thoughtful writing on wine, gastronomy, and travel. The debut issue brings together stories and reflections from Japan and Spain. You can purchase the magazine at: mizanplas.com/store.