Andy Hayler occupies a singular position in contemporary food writing: methodical, independent, and quietly exhaustive in scope. He stands as one of the most consistent food critics in London, and arguably in the world, belonging to a lineage of writers who built their authority slowly, meal by meal, across decades rather than through visibility or provocation. A freelance writer and professional restaurant inspector since 1990, Hayler has constructed a body of work defined less by opinion than by accumulation, comparison, and long-term observation.

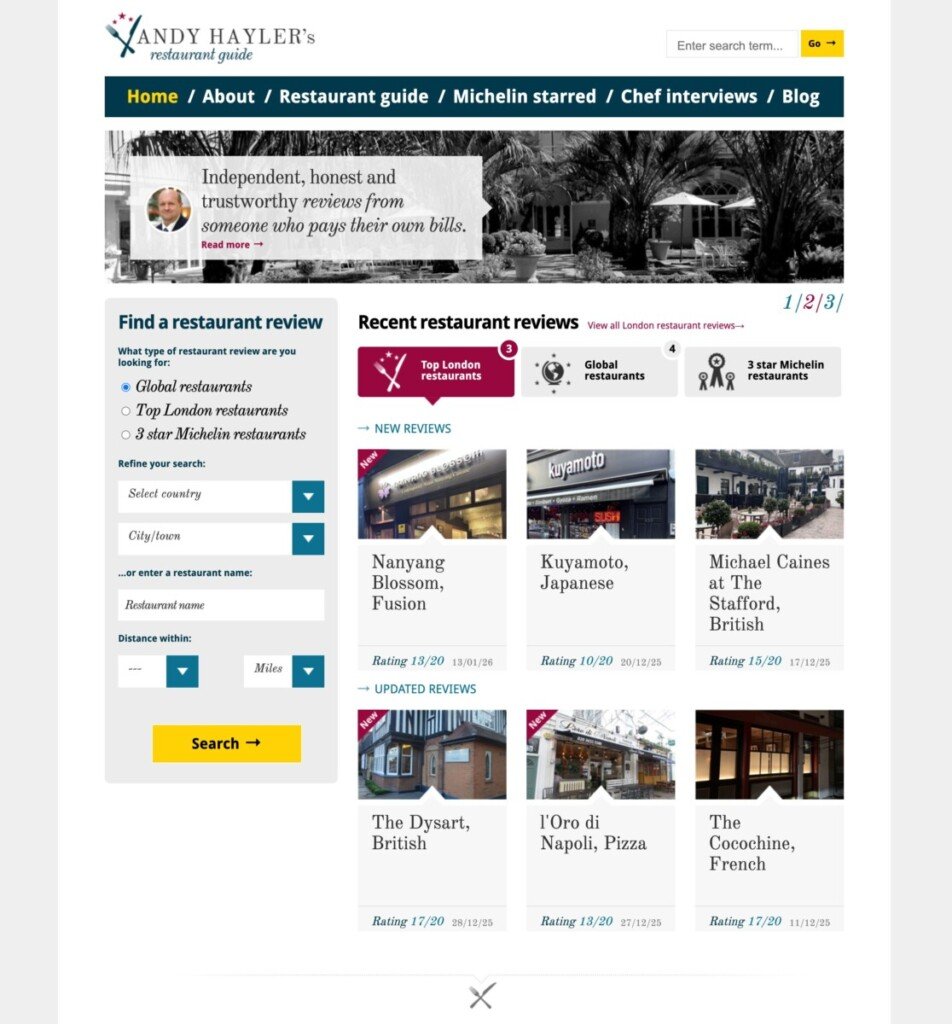

He is best known for his website, andyhayler.com, launched in 1995 and still running today. It remains the longest-established restaurant review website in the world, featuring detailed coverage of more than 2,000 restaurants, roughly half of them in London.

In 2004, he became the first person to have eaten at every restaurant holding three stars in the Michelin Guide worldwide, a distinction he continued to maintain by methodically updating the full global list until international travel was disrupted during the Covid period. This long view, revisiting judgements over decades rather than moments, underpins his writing: comparative, historically informed, and deliberately resistant to fashion.

Alongside his independent work, Hayler has written for Elite Traveller, The Good Food Guide, and National Geographic; contributed extensively to reference works such as 1,001 Restaurants You Must Eat Before You Die; and appeared for seven seasons as a judge on MasterChef. He also authored the London Transport Restaurant Guide. Across formats, his focus remains consistent: precise documentation of cooking, technique, and value, assessed over time rather than through the lens of novelty.

What follows is a conversation informed by that vantage point: less concerned with verdicts than with how standards are established, how they shift, and what endures when reputation is tested repeatedly against experience.

What is your “Madeleine de Proust,” or the first memorable meal that changed your life?

I guess the most influential meal for me was the first time I went to Jamin in Paris. This was in 1986, when Joël Robuchon was cooking at his peak. He’d just gone from one star to two stars to three stars in three years and was getting rave reviews.

Until then, I’d just moved to London after university and had started eating out in good restaurants around London, but I’d never actually been to a proper three-star restaurant. I thought it would be similar to London, maybe a tiny bit better, but I was completely wrong — it was dramatically better. There was nothing like anything I’d had before. I suddenly realised food could be really quite special. So at that point I decided to start exploring other three-star restaurants.

At that time, they were all in Europe. Michelin only started expanding outside Europe in the 2006, with the New York guide. So that meal in the 1990s was the one that really made the difference for me.

And I guess that’s when you started writing about food and restaurants?

A little bit later. I came to London in 1983 after university and started enjoying restaurants.

At the time there was no social media, so you relied on books for restaurant recommendations. There were guides like the Good Food Guide and the Egon Ronay Guide, but the Good Food Guide was the best one, really, and I used it regularly.

For many years now, guides outside Europe have been funded by tourist boards. I’m speaking hypothetically here, but if a tourist authority pays millions for a guide, it inevitably creates pressure. Inspectors aren’t going to return and say, ‘Sorry, none of your restaurants are good enough.’ That doesn’t mean the restaurants are bad — but it does compromise independence, in my view.

They asked for feedback. It was a paper book, with little slips at the back where you could scribble comments and post them in. I did that for a while.

In 1990, I got a call from the editor of the Good Food Guide, Tom Jaine, who said he’d been interested in what I’d been writing and asked if I wanted to meet for dinner. We talked — it was essentially an interview — and he asked if I’d like to become an inspector. It was part-time and different from Michelin: they’d assign you maybe a dozen restaurants a year and pay for dinner for two, and you’d write detailed reports.

I did that for some time. Then in 1994, I started a small restaurant newsletter for friends. I showed it around casually. One of the people who saw it was Clarissa Dickson Wright, later known from The [British cooking series]Two Fat Ladies. At the time she ran a cookery bookshop in Ladbroke Grove called Books for Cooks.

She told me the writing was good and I should try to publish it. I didn’t actively pursue it, but I got lucky and found a publisher — Boxtree, which later became part of Macmillan. That became the London Transport Restaurant Guide, published in 1995.

I knew it would be a one-off book and would date quickly, so I decided to put the content online as well. That was the early internet days — 1995. When I looked back years later, I couldn’t find any restaurant review websites dating earlier than around 2001.

As far as I know, it’s the oldest continuously running restaurant review site. It’s now over 30 years old, with more than 2,000 reviews — roughly half in London and half elsewhere.

Over the years I’ve written for various publications, including National Geographic; contributed to books such as 1,001 Restaurants You Must Eat Before You Die (I wrote about a quarter of it), and appeared on seven epidodes of MasterChef.

As far as I know, you were the first person to visit all three Michelin-starred restaurants in the world. How did that idea come about?

Yes. I did that consistently until the pandemic. I first completed the full list in 2004 — there were 67 at the time, all in Europe. From the 2000s onwards, Michelin expanded internationally. I kept the full roster updated every two years.

I did New York when it launched, then Tokyo, Hong Kong, and so on. I kept doing that through 2010, 2012, 2014, right up until the end of 2019.

When the pandemic hit in early 2020, it became physically impossible. China was inaccessible and Japan remained closed far longer than Europe. At that point, after about 16 years, I decided that was enough. I still visit some new three-stars, but not all of them.

Part of that decision was also Michelin’s business model change. In the pre-Internet era, Michelin funded itself through guide sales — millions annually in France alone. With declining book sales, they restructured and realised the Michelin brand had value to tourist boards.

There are maybe two dozen genuinely incontestable three-star restaurants worldwide.

For many years now, guides outside Europe have been funded by tourist boards. I’m speaking hypothetically here, but if a tourist authority pays millions for a guide, it inevitably creates pressure. Inspectors aren’t going to return and say, “Sorry, none of your restaurants are good enough.”

That doesn’t mean the restaurants are bad — but it does compromise independence, in my view.

How do three-Michelin starred restaurants vary around the world? Do you think some restaurants deserve three stars more than others?

Yes. It’s never been a science. Judgement is subjective. The advantage of my guide is consistency — it’s one person, one set of criteria.

Twenty years ago, there were anomalies, but the logic was clearer. Germany, for example, had exceptionally strong top-level restaurants: Victor’s Fine Dining, Sonnora, Schwarzwaldstube. In comparison, some later additions in other countries didn’t feel in the same league.

That clarity has weakened since the funding model shifted.

Shanghai in 2018 was a turning point for me. The guide launched with six two-stars and one three-star. I visited with three Chinese food writers and specialists. Apart from one European restaurant, we all agreed the Chinese two-stars wouldn’t earn a single star elsewhere.

That was when I stopped chasing the full list.

And London?

London is a good example. I don’t think there is a truly world-class three-star restaurant there.

There are maybe two dozen genuinely incontestable three-star restaurants worldwide — places like Troisgros, Kei, Victor’s Fine Dining, Sonnora, Schwarzwaldstube and Hôtel de Ville. None in London are in that bracket for me.

I score out of 20, and London’s three-star restaurants don’t score higher than 17 for me. The Ritz, which is now two-star, actually scores higher at 18/20.

If I look at the restaurants I actually go back to in London, most of them are one-star or unstarred. The Ritz is a good example. Michelin didn’t give iat even one star for a long time. The food didn’t change, but eventually it received one star and then two. In my view, it should have had two stars ten years earlier.

I regularly return to places like The Dysart, Cochin and Cornus. These are restaurants I genuinely enjoy going back to. Row on 5 also stands out, with clear Japanese influence and strong technique.

I still visit Gordon Ramsay, Alain Ducasse and Hélène Darroze. They’re good restaurants, but for me they sit at a solid two-star level rather than being true three-star destinations.

Chefs borrow ideas, techniques and ingredients and adapt them to their own cooking.

How does your scoring system work [on andyhayler.com]?

I adapted the Good Food Guide methodology. I score each dish and take the arithmetic average.

I assess presentation, ingredient quality, technique, and harmony. Michelin’s criteria are similar, though they exclude presentation and include “chef personality”, which I find vague. I don’t score ambience or service, and that’s a deliberate decision.

Ambience is an extraordinarily personal thing. If I say I like the décor of the Ritz, someone else might say they hate it because it feels old-fashioned — and they’re not wrong. It’s just an opinion.

Service works the same way. Some people want very attentive service: explanations, conversation, guidance through the dishes. Others might be on a date or in a business meeting and want to be left alone.

A really good waiter senses that and adjusts accordingly. Because expectations vary so much, I don’t think service can easily be scored objectively. I talk about it in the review if it’s notably good or bad, but I don’t include it in the score.

How do you maintain consistency over time?

I think the main advantage is that it’s just one person rather than a team. When it’s one person writing, you’re going to get a consistent view automatically. I don’t really have to do anything special to be consistent — I just have to be honest and apply the same criteria every time.

It’s much more difficult for organisations like Michelin, where you have a team of inspectors. Even if they’re well trained, there are always going to be differences of opinion. I saw that myself at the Good Food Guide, where inspectors would sometimes disagree when discussing scores. So consistency is simply much easier when it’s one person.

And objectivity? Especially if you don’t like the particular style?

I always come back to the criteria. I look at presentation, ingredient quality, technique and harmony, regardless of whether the style of food appeals to me personally.

Like anyone, I have preferences — I tend to enjoy classical cooking — but that doesn’t mean I can’t recognise excellence in other styles. I’ve given very high scores to food that isn’t my personal taste. For example, I scored Oud Sluis very highly when it was run by Sergio Herman, even though that wasn’t really my style of cooking. Objectively, it was outstanding.

So even if it’s not something I’d necessarily rush back to, I can still see when something works extremely well and score it accordingly.

You were one of the first food bloggers and restaurant critics in the world. How has the restaurant world changed since you started writing about food.

Restaurants have always gone through fashions, so there are different phases and trends. When El Bulli became influential, many chefs started experimenting with similar techniques. Later on, when Noma became very well known, fermentation and a more Nordic style of cooking spread widely. Now it’s Japanese techniques and ingredients — maybe not Japanese cuisine as such, but techniques — that appear in fine-dining restaurants almost everywhere.

I don’t really have to do anything special to be consistent — I just have to be honest.

You see it in Stockholm, you see it in London, you see it across Europe. Chefs borrow ideas, techniques and ingredients and adapt them to their own cooking.

A good example is Michel Bras’ gargouillou dish. I’ve had versions of that dish many times in different restaurants around the world. They’re rarely exact copies, but they’re clearly inspired by the original idea: multiple vegetables, different textures, some raw, some cooked, some fermented, some pickled, all brought together on the plate. I’ve had variations in Japan, in Hong Kong and across Europe.

What’s really changed is the speed. Thirty years ago, unless you travelled, it was difficult to know what was happening in other countries. A cook in Italy might not know what chefs in Japan or Spain were doing. Now, with the internet and social media, chefs see dishes almost instantly. Even without recipes, they can see an idea and think, “That looks interesting — I’ll try something like that.” As a result, trends spread and evolve much more quickly than they used to.

And restaurant criticism today?

All of these changes have happened gradually, but they’ve had a big impact. Print guides really struggled. The Good Food Guide, for example, used to sell well over 100,000 copies a year, then that dropped to around 60,000, and eventually it became very difficult to sustain. I think they were down to around 16,000 copies before they were sold for very little money and moved to a purely digital format.

That must have been a similar story for many other print guides. Some still exist, but they’ve had to change their business models. Gault & Millau, for example, operates as a franchise in many countries, where local operators run it and make their own money through events and sponsorships rather than book sales.

The biggest change, though, has been the rise of online voices — bloggers, social media, Instagram, and so on. Thirty or forty years ago, if a restaurant was reviewed by someone like Fay Maschler in London, that could make or break it. A single critic had enormous inflauence.

Now criticism is much more democratised. Anyone can write about food, post photos, share opinions. You can choose who you follow, whose taste you trust, and whose opinions align with yours. If you stop agreeing with someone, you simply unfollow them.

It’s never been a science. Judgement is subjective. The advantage of my guide is consistency — it’s one person, one set of criteria. When you have teams of inspectors, even if they’re well trained, differences of opinion are inevitable.

I actually think that’s a good thing. Over time, the people producing thoughtful, consistent content tend to keep an audience, and the ones who don’t tend to fade away. Quality, to some extent, sorts itself out.

Are you still as excited about discovering and reviewing new restaurants as you were at the beginning?

Yes, absolutely. I’m always optimistic when I go to a new restaurant. If I’ve read that it’s good, I go in hoping it really will be. Sometimes it doesn’t live up to expectations, and that’s just part of life.

But other times you find something special, and that’s still incredibly rewarding. A good example was The Greenhouse in Dublin, which I visited when it had just opened. Almost nobody had written about it at the time. I went in without expectations and was genuinely surprised by how good it was. I scored it very highly, well before Michelin recognised it.

More recently, places like Koyal in Surbiton give me that same feeling. It’s not in a fashionable area, it’s not surrounded by hype, but the food is outstanding. Helping restaurants like that gain some recognition still gives me enormous pleasure.

What are your gold standard three-Michelin starred restaurants in the world? Could you mention a few of your favourites?

If we’re talking about fine dining, Christian Bau remains the benchmark for me. I’ve eaten there many times over the years, and the consistency is extraordinary. The ingredients, the technique, the balance — everything is flawless.

There are others in that same tier. Troisgros is still exceptional, even after several generations. In Japan, places like Sushi Saito and Sushi Arai are, in their own way, almost perfect. They do something very specific, but they do it at an incredibly high level.

Among newer restaurants, Jan in Munich stands out. I’ve had several meals there, and it’s genuinely world-class. In general, anything that scores 20 on my site belongs in that top category.

Which trends do you think should stay, and which should go?

Anything that genuinely improves the dining experience should stay. High-quality ingredients, better sourcing, respect for produce — those are all positive developments. Using local produce where possible is also important, not just for quality but because it supports farmers and producers who are willing to work at a high level.

I’m less enthusiastic about trends that are clever but don’t improve flavour. There was a period where a lot of chefs were focused on technical manipulation of ingredients — changing textures, shapes, appearances — and sometimes it felt like an intellectual exercise rather than something that tasted better.

With ants, once you’ve had them once, the shock wears off. They don’t contribute much flavour, and often they’re there simply to provoke a reaction. At that point, I think you can move on.

I still value proper craft: making your own stocks, your own sauces, doing the basics well. That’s becoming rarer, even in high-end restaurants, but for me it’s fundamental. That’s what restaurants are for — doing things properly that you wouldn’t or couldn’t do at home.

Ants on dishes?

I’ve eaten all sorts of things over the years — live ants, ant larvae, scorpion, exotic meats, all kinds of unusual ingredients in different countries. I don’t have a problem with any of that in principle.

The question is whether it adds anything. With ants, once you’ve had them once, the shock wears off. They don’t contribute much flavour, and often they’re there simply to provoke a reaction. At that point, I think you can move on.

One dish that still haunts you, for the right reasons?

That’s a difficult question, because there have been many over the years. But one that has stayed with me for a very long time is Marco Pierre White’s Pyramide dessert at Harvey’s. It was visually striking and technically clever, but also delicious — the balance between sweetness and acidity was memorable.

Another is a pasta dish at Le Cinq. It’s architecturally astonishing: the pasta stands upright like a small structure, with a rich filling inside and often finished with mushrooms or black truffles. You look at it and wonder how it’s even possible to make, and then you taste it and everything works perfectly.

Those are the kinds of dishes that stay with you for decades.